Thank you for that question, Maddy!

Summer day, sandwiches on the deck, chit chat, during which my friend Maddy asks: “I’ve heard of Jules Verne and Robert Louis Stevenson, but not William Morris. What is he doing in your book?”

“Very good question! Thank you for asking!” In this case, I really mean it. Here is more or less how I responded:

Verne and Stevenson are well known because nothing has the lasting power of a good story. They wrote yarns that were best-sellers in their day and still are. Even if you have never read Verne’s 20000 Leagues under the Sea or Around in the World in 80 Days, you have heard of them and have some idea of the plot from the titles. It’s the same with Stevenson’s Treasure Island and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

William Morris was famous in his own day as a writer, but it was as author of a long narrative poem titled The Earthly Paradise. He was a serious contender for Poet Laureate of the realm mainly on the basis of this work. But hardly anyone reads long poems anymore, and even English majors rarely read this one.

Instead, Morris lives on as a writer indirectly through the work of others. He was a folklorist who retrieved and reworked tales from many times and places, becoming especially fond of Norse sagas. After many experiments working with these raw materials, he invented a new prose form, which we now call fantasy. He wanted to tell of heroic quests that require core human virtues, especially courage, but that had become difficult or impossible to carry out on the planet as we know it.

Some of Morris’s fantasy novels still attract readers (especially The Well at the World’s End), but their loose plots and archaic language make them tough going for many. Even if they are not best-sellers, however, they have been an enormous influence on later writers–most notably J.R.R. Tolkien in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Morris’s invention of fantasy adventures has swept the world in the form of books, movies, and games.

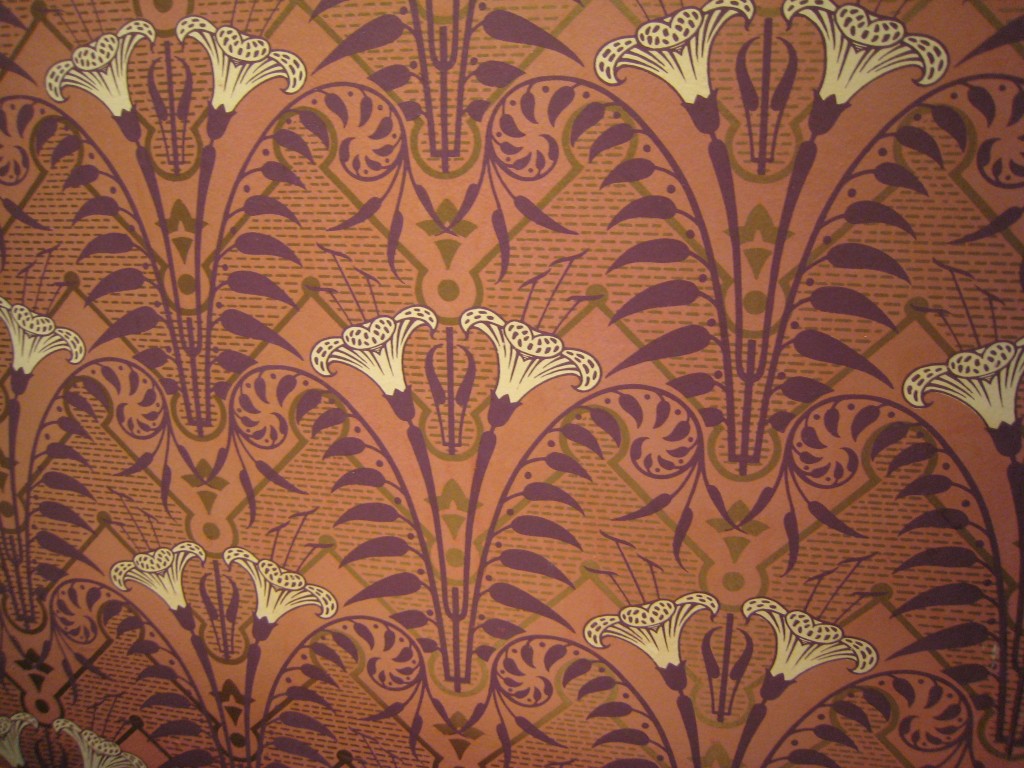

In a second way Morris’s work is all around us in unrecognized form: his work as a designer of household furnishings and domestic art. When Maddy asked “Why Morris?”, I answered in part by taking her to a bedroom in our house decorated with Morris-designed wallpaper:

The design is old but the wallpaper is relatively new. The firm that Morris founded to produce such goods went out of business only at the beginning of World War II; his patterns for wallpaper, fabrics, and other domestic goods are still being made by other manufacturers. I also took Maddy to our sun room to see the “Morris chair” there, probably made in the 1880s, and coming to me from my grandparents’ house. It is what we would now call a reclining chair, using a simple but effective movable bar to adjust the tilt of the back:

The usual way of describing Morris as a designer is to say he is the inventor of functionalism, the concept that beauty emerges from utility. In this general sense his principles of design have long since overflowed their original cultural home of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the late l9th century. They are just as relevant for the design of electronic gadgets as for that of household furnishings.

Even more important, though, is Morris’s conviction that beauty and utility depend upon the joy of the workman in his labor. Unless making things engaged human creativity and gave a sense of purpose, they were not worth making.

This conviction–that the needs of producers are paramount–led Morris to become a revolutionary socialist–and in the process invented an entirely new kind of socialism. He defined the needs of the producers not primarily by material measures, but by the soul-satisfaction they found in their work. He treasured the beauty of the visible landscape and the vitality of the non-human world at a time when these qualities were hardly registered by other socialists. When they accused him of “sentimentalism,” Morris responded that he was indeed a “sentimental socialist” and proud of it.

I wrapped up my answer to Maddy by saying that it is the combination of these three accomplishments—inventor of fantasy, of functional design, and of a new kind of politics–that gives Morris a place of honor in my book. Thinking about it more since, I realize that what most intrigues me about Morris is not how these three creative contributions converged in his life, but how they do not. His moral sensibilities contradict each other from beginning to end.

Morris hates the way human weaknesses and failings have overrun the world. He is convinced that the triumph of human empire is profoundly wrong, in the fantasy literature sense of wrongness. Yet he also wants to be realistic, to face the facts, to avoid evasion. He is convinced that what he cares about most–attachments to the deep human past and to the non-human life of the earth–are being lost, rapidly and irretrievably. He will lose. Yet he wants to find happiness in the world. It is too wide and wonderful a place to dwell in misery, and yet happiness becomes more difficult to find as humankind more and more dominates the world.

How does one hold on to all these convictions at once? This is the question Morris raises and that we continue to live with today. Good question. Thanks for asking.